|

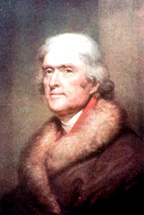

George Washington. Vice-President of the United States of America. President of the United States (1801 to 1809) |

|

Historians might want to add other accomplishments--for example, his distinction as an architect, naturalist, and linguist--but in the main they would concur with his own assessment. Elected to the Second Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia, Jefferson was appointed on June 11, 1776, to head a committee of five in preparing the Declaration Of Independence. He was its primary author, although his initial draft was amended after consultation with Benjamin Franklin and John Adams and altered both stylistically and substantively by Congress. Jefferson's reference to the voluntary allegiance of colonists to the crown was struck; also deleted was a clause that censured the monarchy for imposing slavery upon America. Based upon the same natural rights theory contained in A Summary View, to which it bears a strong resemblance, the Declaration of Independence made Jefferson internationally famous. Years later that fame evoked the jealousy of John Adams, who complained that the declaration's ideas were "hackneyed." Jefferson agreed; he wrote of the declaration, "Neither aiming at originality of principle or sentiment, nor yet copied from any particular and previous writing, it was intended to be an expression of the American mind." Returning to Virginia late in 1776, Jefferson served until 1779 in the House of Delegates, one of the two houses of the General Assembly of Virginia--established in 1776 by the state's new constitution. While the American Revolution continued, Jefferson sought to liberalize Virginia's laws. Joined by his old law teacher, George Wythe, and by James Madison and George Mason, Jefferson introduced a number of bills that were resisted fiercely by those representing the conservative planter class. In 1776 he succeeded in obtaining the abolition of entail; his proposal to abolish primogeniture became law in 1785. Jefferson proudly noted that "these laws, drawn by myself, laid the ax to the foot of pseudoaristocracy." |

|

|

~ Wartime Governor of Virginia ~ The death of his wife, on Sept. 6, 1782, added to Jefferson's troubles, but by the following year he was again seated in Congress. There he made two contributions of enduring importance to the nation. In April 1784 he submitted Notes on the Establishment of a Money Unit and of a Coinage for the United States in which he advised the use of a decimal system. This report led to the adoption (1792) of the dollar, rather than the pound, as the basic monetary unit in the United States. As chairman of the committee dealing with the government of western lands, Jefferson submitted proposals so liberal and farsighted as to constitute, when enacted, the most progressive colonial policy of any nation in modern history. The proposed ordinance of 1784 reflected Jefferson's belief that the western territories should be self-governing and, when they reached a certain stage of growth, should be admitted to the Union as full partners with the original 13 states. Jefferson also proposed that slavery should be excluded from all of the American western territories after 1800. Although he himself was a slaveowner, he believed that slavery was an evil that should not be permitted to spread. In 1784 the provision banning slavery was narrowly defeated. Had one representative (John Beatty of New Jersey), sick and confined to his lodging, been present, the vote would have been different. "Thus," Jefferson later reflected, "we see the fate of millions unborn hanging on the tongue of one man, and heaven was silent in that awful moment." Although Congress approved the proposed ordinance of 1784, it was never put into effect; its main features were incorporated, however, in the Ordinance of 1787, which established the Northwest Territory. Moreover, slavery was prohibited in the Northwest Territory. ~ Minister to France ~ Jefferson suspected Hamilton and others in the emerging Federalist Party of a secret design to implant monarchist ideals and institutions in the government. The disagreements spilled over into foreign affairs. Hamilton was pro-British, and Jefferson was by inclination pro-French, although he directed the office of secretary of state with notable objectivity. The more Washington sided with Hamilton, the more Jefferson became dissatisfied with his minority position within the cabinet. Finally, after being twice dissuaded from resigning, Jefferson did so on Dec. 31, 1793. At home for the next three years, Jefferson devoted himself to farm and family. He experimented with a new plow and other ingenious inventions, built a nail factory, commenced the rebuilding of Monticello, set out a thousand peach trees, received distinguished guests from abroad, and welcomed the visits of his grandchildren. But he also followed national and international developments with a mounting sense of foreboding. "From the moment of my retiring from the administration," he later wrote, "the Federalists got unchecked hold on General Washington." Jefferson thought Washington's expedition to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion (1794) an unnecessary use of military force. He deplored Washington's denunciation of the Democratic societies and considered Jay's Treaty (1794) with Britain a "monument of folly and venality." Thus Jefferson welcomed Washington's decision not to run for a third term in 1796. Jefferson became the reluctant presidential candidate of the Democratic-Republican party, and he seemed genuinely relieved when the Federalist candidate, John Adams, gained a narrow electoral college victory (71 to 68). As the runner-up, however, Jefferson became vice-president under the system then in effect. Jefferson hoped that he could work with Adams, as of old, especially since both men shared an anti-Hamilton bias. But those hopes were soon dashed. Relations with France deteriorated. In 1798, in the wake of the XYZ Affair, the so-called Quasi-War began. New taxes were imposed and the Alien And Sedition Acts (1798) threatened the freedom of Americans. Jefferson, laboring to check the authoritarian drift of the national government, secretly authored the Kentucky Resolution. More important, he provided his party with principles and strategy, aiming to win the election of 1800. |

|

|

|

|

John Trumbull (1756-1843) Oil on panel, 1788 National Portrait Gallery - Smithsonian |

|

|

|

In the final 17 years of his life, Jefferson's major accomplishment was the founding (1819) of the University of Virginia at Charlottesville. He conceived it, planned it, designed it, and supervised both its construction and the hiring of faculty. The university was the last of three contributions by which Jefferson wished to be remembered; they constituted a trilogy of interrelated causes: freedom from Britain, freedom of conscience, and freedom maintained through education. On July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson died at Monticello. |

Author: Morton Borden

Portrait: Stuart, Gilbert (1755 - 1828). Thomas

Jefferson, c. 1821. Oil on wood, National Portrait Gallery.

Bibliography: Boyd, Julian P., et al., eds., The Papers

of Thomas Jefferson, 60 vols. (1950) and Public and Private

Papers (1990); Brodie, Fawn, Thomas Jefferson: An Intimate

History (1974; repr. 1981); Cunningham, Noble E., In Pursuit

of Reason: The Life of Thomas Jefferson (1987); Dabney, Virginius,

The Jefferson Scandal: A Rebuttal (1981); Levy, Leonard,

Jefferson and Civil Liberties (1972; repr. 1989); McDonald,

Forrest, The Presidency of Thomas Jefferson (1976); McLauglin,

J., Jefferson and Monticello (1988); Malone, Dumas,

Jefferson and His Time, 6 vols. (1948-81); Mayo, Bernard,

Thomas Jefferson and His Unknown Brothers (1981); Miller,

John C., The Wolf by the Ears: Thomas Jefferson and Slavery

(1980) and Jefferson and Nature (1988); Peterson, Merrill

D., Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation (1970; repr. 1986);

Tucker, Robert W., Empire of Liberty: The Statecraft of Thomas

Jefferson (1990); Wills, Garry, Inventing America: Jefferson's

Declaration of Independence (1978).

Facts About Thomas Jefferson: 3d President

of the United States (1801-09)

Nickname:

"Man of the People"; "Sage of Monticello".

Born: Apr. 13, 1743, Shadwell plantation, Goochland (now

in Albemarle) County, Va.

Education: College of William and Mary (graduated 1762).

Profession: Lawyer, Planter.

Religious Affiliation: None.

Marriage: Jan. 1, 1772, to Martha Wayles Skelton (1748-82).

Children: Martha Washington Jefferson (1772-1836); Jane

Randolph Jefferson (1774-75); infant son (1777); Mary Jefferson

(1778-1804); Lucy Elizabeth Jefferson (1780-81); Lucy Elizabeth

Jefferson (1782-85)

Political Affiliation: Democratic-Republican.

Writings: Writings (10 vols. 1892-99), ed. by Paul

L. Ford; The Papers of Thomas Jefferson (1950- ), ed. by

Julian P. Boyd, et al.; Notes on the State of Virginia 1781

(1955), ed. by William Peden; Autobiography (1959), ed.

by Dumas Malone

Died: July 4, 1826, Monticello, near Charlottesville, Va.

Buried: Monticello, near Charlottesville, Va.

Vice-President: Aaron Burr (1801-05); George Clinton (1805-09).

Cabinet Members: Secretary of State: James Madison.

Secretary of the Treasury: Samuel Dexter (1801); Albert

Gallatin (1801-09).

Secretary of War: Henry Dearborn.

Attorney General: Levi Lincoln (1801-04); John Breckinridge

(1805-06); Caesar A. Rodney (1807-09).

Secretary of the Navy: Benjamin Stoddert (1801); Robert

Smith (1801-09).